Don Wilkinson, Correspondent

Published Aug 6, 2022

DATMA likes big themes

For four years the self-proclaimed “museum without walls” (whose name is an acronym of Design Art Technology MAssachusetts) has presented large-scale dynamic, ambitious and all-encompassing cultural, scientific and socially-oriented exhibitions.

In partnership with cultural and educational institutions, local and not-so-local artists, and many others, DATMA has offered up truly big subjects for consideration. In 2019, it was Wind.

In 2020, it was Light. Last year, it was Water.

All three themes have particular significance for New Bedford. To a great degree, wind and water determine the fortune of the fishing fleet and connected industries. The city’s motto “lucem diffundo” (Latin for “I diffuse light”) alludes to the whale oil that kept the lanterns burning more than a century ago.

The overarching theme for 2022 and 2023 is Shelter. But the connection to New Bedford may not seem so clear as in previous years. Again — big theme. How about the leeward side of the fishing vessel? That gold standard hurricane dike? The safehouses along the Underground Railroad in which runaway slaves sought refuge and a new life? The communal havens for the homeless, the hungry and the domestically abused? The harbor itself when the bridge is opened to welcome boats seeking any port in a storm when the storm is in pursuit?

Ancestral Procession by Alison Wells

Ericka Huggins Liberation Groceries by Lmerchie Frazier

Under DATMA’s aegis, some of those subjects are being explored at present. Some may be next year; maybe some not at all. It is an expansive undertaking but I will focus — for now — on only one particular element and that is the exhibition called “Sheltered” at the University Art Gallery at the College of Visual and Performing Arts, UMass Dartmouth Star Store Campus.

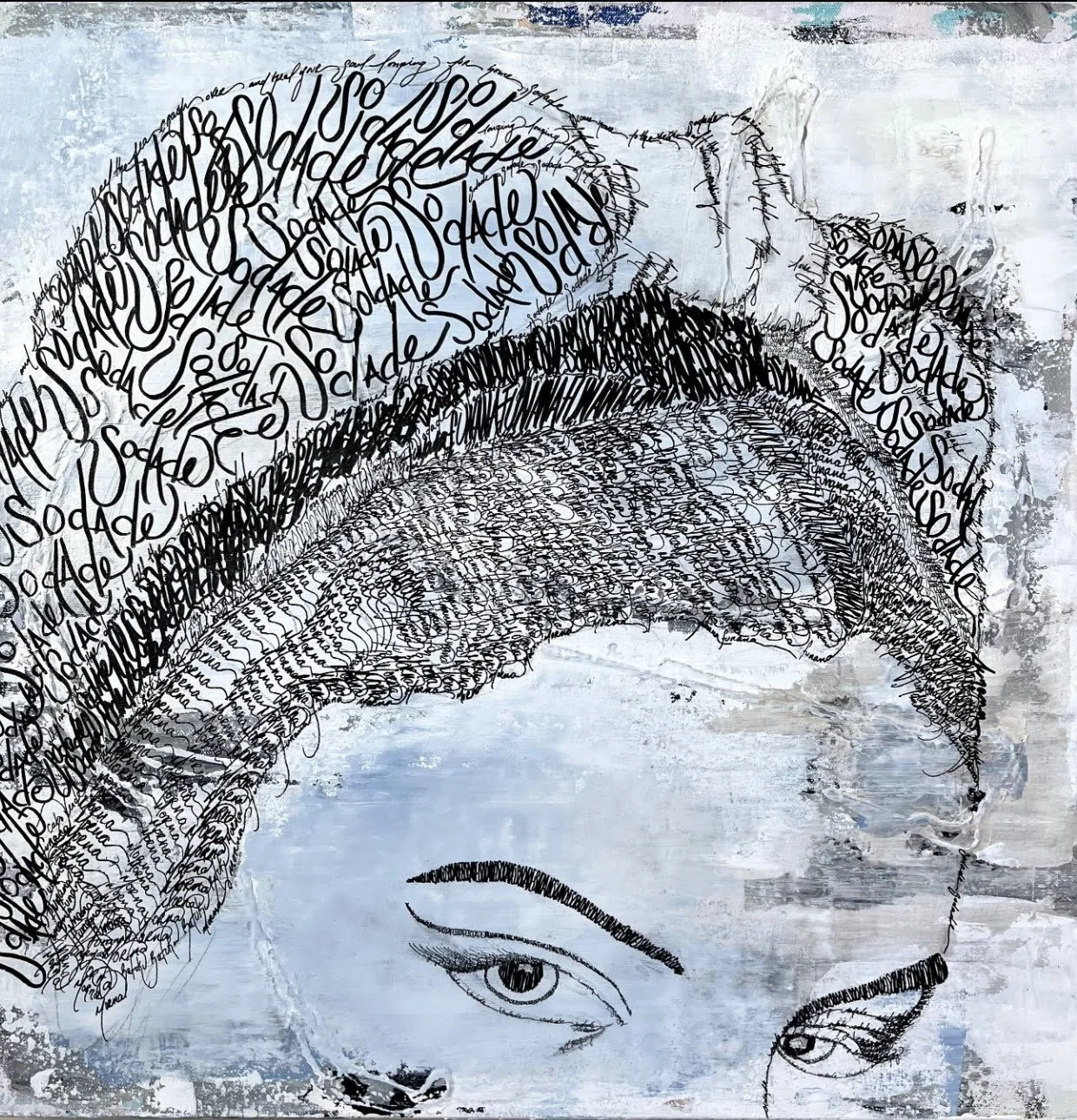

Sodade by Meclina Priestly

It features work by contemporary women artists of color with diverse cultural backgrounds. Curated by Trinidad-born New Bedford painter and collagist Alison Wells, in collaboration with the gallery’s director Viera Levitt, it makes one think about the very concept of shelter in unanticipated ways.

Shelter is one of the three most primal necessities of life, right alongside food and water. But to be “sheltered” implies more than just four walls and a roof. It can mean to be protected from the troubles, annoyances, and sordidness of the world.

Curator Wells, who is also an exhibiting artist in “Sheltered,” “noted that she wanted to explore the subject through the lens of women artists, particularly from the African Diaspora, in order to shed a unique light on ‘Blackness and Womanhood’ and what that means as a relevant topic in today’s world.”

Artist L’Merchie Frazier, an internationally recognized visual and performance artist with work in the Smithsonian and the White House as well as many other institutions, asked in her artist’s statement, “Sheltered from? Sheltered by? Sheltered with? Sheltered for? Sheltered where?” All significant questions, sometimes with difficult answers.

Frazier presented a quilted portrait entitled “Ericka Huggins - Liberation Groceries” featuring a woman in a red jacket and big hoop earrings holding a brown paper bag from which salad greens and a dozen eggs protrude. On the bag itself is a “Panther Power” decal.

Activist Huggins was the director of the Black Panthers’ Intercommunal Youth Institute in Oakland, California in the 1970s. The image suggests that the comfort of community and a commitment to food security is a kind of shelter as well.

Photographer Gloretta Barnes presents a series of images of ordinary people going about their lives in Ghana and Nigeria. A particularly striking capture is that of two women, likely a mother and daughter, sitting on a bench in front of an elaborate mural, perhaps depicting tribal affiliation.

In “Matriarch,” the older woman, in a vivid purple headdress, looks like a no-nonsense type, particularly if she thought her young adult daughter‘s safety or security might be at risk. Barnes describes herself as “an African woman in America” with cultural connections to the past and the present. The past can be a shelter, as can be the present, and with good fortune, shelter may be the future.

Meclina Priestley is a painter, calligrapher and micrographer who displays a series of works which she describes as being a reflection of “morna,” a longing for connection with her Cape Verdean roots. Her large-scale washes are displayed alongside a tethered magnifying glass so that viewers can read the incredibly small script that makes up the shadows, curves and locks of hair that make up her portraits.

Although Priestley has never been to Cape Verde, her wistfulness and her nostalgia for something she has never experienced firsthand is palpable. A close examination of the topless woman (her back to the viewer) wil reveal “my soul is longing…” across her shoulder. It reads “We are this moment…standing by the sea New Bedford to Fogo” in the small of her back. Desire can provide shelter too.

Wells displays two paintings — “New Bedford Roots” and “Ancestral Procession” — that like several of her co-exhibitors suggest that earnest remembrance is a source of comfort and that comfort is shelter. But her “White Field” is far more straightforward. It features thickly-applied loose rectangles, in ecru and beige on a slightly whiter field.

The Key by Ekua Holmes

It can be viewed as a drunken bird’s eye of a city grid, complete with rooftops, intersections and too-close neighbors. Or maybe, it’s building materials, the very stuff of shelter: white-washed bricks or cinder blocks.

Culling the childhood experiences — Colorforms, paper dolls and putting S&H green stamps into books — that made her a collagist, Ekua Holmes has the most traditional depiction of shelter in the show. As brightly hued as a happy children’s book, she depicts fond memories of butterflies, flowers, shared house keys, parents swinging a tiny daughter between them, a girl jumping rope and a boy riding a bike. It is happiness itself.

The highlight of the exhibition is Corrine Spencer’s dreamy “Splendor,” a mixed media, site-specific installation that incorporates hanging translucent fabric, projected moving images and sound. It is aesthetically and emotionally striking. In it, a woman (the artist herself) frolics in the woods and lies with delight in a gurgling brook.

Spencer notes that her aim is to place Black women at the heart of a transcendent experience and she asks viewers of all backgrounds “to connect to transcendence through Blackness, reaching beyond the borders of their bodies into the vast universe, as black, radiant and endless as space.”

Transcendence is shelter too.

“Sheltered” is on display at the University Art Gallery, 715 Purchase St., New Bedford until Sept. 8.